Silversmith Hans Christensen (Danish, 1924-1983) left an indelible impact on the field of metalwork in the United States. In the latter portion of the twentieth century his influence was felt not only in the classroom, but in the studio as well. Christensen’s masterful hollowware designs, that embrace simplicity, clean lines, and natural curves, “…put a great deal of importance on the play of light and shadow, balance for the eye as well as for the hand…,” and “…function which is so often forgotten.”[i] “Silver [was] more to [Christensen] than mere decoration. It [was] a wonderful metal capable of being made into any number of forms.”[ii]

The Kamm Teapot Foundation has two important examples of Christensen’s work in its collection. Both objects reflect his deep knowledge of silversmithing practices and his talent as a designer. For this blog post we will share a little bit about Christensen’s life and take a closer look at these exquisite works.

Background and Beginnings

Christensen was born into a “very conservative” family in the cosmopolitan city of Copenhagen.[iii] His father wanted his son to follow in his footsteps and become an accountant.[iv] However, at age sixteen Christensen announced that he wanted to be a sculptor. His father responded, “Not over my dead body.”[v] Therefore, a compromise was made, and Christensen was given permission to pursue a career as a silversmith. His parents felt silversmithing would offer “more controlled” “more substantial” employment.”[vi]

In 1939, the year that World War II commenced, Christensen began his studies in Copenhagen. At night he took classes at the School for Arts and Crafts and during the day he launched into a five-year apprenticeship at the highly acclaimed firm of silversmith Georg Jensen. These experiences provided Christensen with substantial theoretical as well as practical training. For his final project as an apprentice, which is called a journeyman’s piece, Christensen was granted the freedom to design and construct a work on his own. His creation, a stunning teapot and warmer, highlighted all his skills as a silversmith and garnered attention from the highest levels in Denmark.

Journeyman Teapot and Warmer

Christensen’s teapot and warmer helped him earn his silversmith certificate in March of 1944. Additionally, the work was awarded two silver medallions for execution and for design. Presented to Christensen by King Frederick IX of Denmark, these medallions were a rare and extraordinary honor.[vii] It was particularly remarkable for one apprentice to receive two. This had not occurred since the nineteenth century.

The Kamm Collection is fortunate enough to have not only Christensen’s teapot and warmer, but the two medallions as well. The teapot contains a simple ovoid body with flowing curves, a short tubular spout, and a dramatically curving handle. Upon first glance, it appears the teapot almost floats upon its warmer whose upright prongs resemble the leaves and flowers of a cattail plant.[viii] Rosewood is utilized on a small cylindrical finial, the base of the warmer, and the handle that hovers over the form. Christensen “liked the warm, gratifying compliment of rosewood and silver” as well as a satin finish instead of a machine-like high polish.[ix]

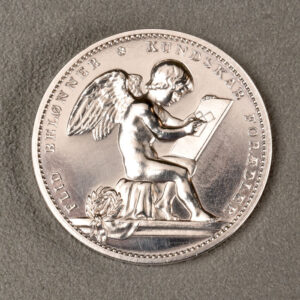

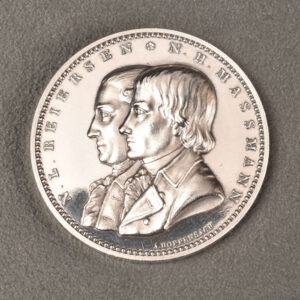

The silver medallions that Christensen received feature reliefs. One has a winged cherub with a drawing board and double figural busts.[x] The other awarded by the Copenhagen Craftsmen’s Association has a seated figure holding a wreath. This seated figure could be Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom, arts, crafts, and industry. At her feet are tools of different trades. The text on the medallions further describes the awards and both medallions have cases with Christensen’s name inscribed in gold.

Advanced Training and Georg Jensen

After finishing his apprenticeship, Christensen continued his education at the College of the Technical Society in Copenhagen and the School of the Arts and Crafts in Oslo, Norway.[xi] During this period, he fine-tuned his design skills and prepared for a career in industry. Christensen explained that the Technical Society taught you to “…design things that could be sold.”[xii] It is one thing “to design [a] thing for your own fantasy,” but it is another matter to consider the marketability of that object.[xiii] This training was undoubtedly considered when Georg Jensen hired Christensen as lead silversmith in his prototype department.

From 1952-1954 Christensen worked with many of Jensen’s top designers in this position including Magnus Stephensen, Sigvard Bernadotte, and Henning Koppel. In 1952 he traveled to the United States as the firm’s representative for an exhibition featuring Jensen’s work at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York. Christensen had created approximately eighty percent of the Jensen objects on view. Because of this exhibition at MOMA, he had the opportunity to meet many pivotal figures involved in the American Studio Craft Movement. These individuals such as Aileen Osborn Webb encouraged Christensen to come to the United States to teach at the School for American Craftsmen in New York.[xiv]

Relocated in America

Christensen received multiple letters from the United States persuading him to relocate.[xv] Then, he got a Sunday morning visit from Folmer Trolle Prip persuading him to go.[xvi] Prip’s son, the silversmith John Prip, was already in America. This meeting helped finalize Christensen’s decision. He left Denmark in 1954 to teach at the School for American Craftsmen. For the next twenty-nine years Christensen taught there influencing generations of students. In 1976 he was chosen by the school to be the first person to hold the Charlotte Fredericks Mowris Professorship of Contemporary Crafts.

In 1958 Christensen submitted a sterling silver coffee service for an exhibition at the World’s Fair in Brussels, Belgium. A coffee pot from that design is now in the Kamm’s Collection. It is a clean, tapered, circular form which swoops out at the top to incorporate a short-tapered spout. From a bird’s-eye view the coffeepot, with its concave top, appears tear-drop shaped. However, the most interesting aspect of this work is its rosewood handle. Unlike typical handles, it is attached upright behind a hinged lid. This positioning received a great deal of attention in Brussels. In addition, this design appeared to be a continued focus for Christensen. He recreated versions of this concept many times following the Fair always considering the object’s functionality.[xvii]

Although Christensen submitted work for specific exhibitions like the World’s Fair, he primarily focused on hollowware commissions for clients. These works, which were a combination of simplicity and technical virtuosity, allowed him to “[make] objects for people that specifically defined their personality and individuality.”[xviii] In 1982 Christensen explained, “Hollowware is very time-consuming, and it is bigger pieces of work. So, I limit myself to, at the highest, twenty pieces a year…I don’t advertise. I try almost to hide as much as possible.”[xix]

In the late 1970s and 1980s Christensen had branched out creating organic brass sculptures that played with movement. Today these remarkable works as well as his silver objects can be found in public and private collections all over the world. Christensen died in 1983 in an automobile accident. The untimely death of this “gifted artist, teacher, and person…created an unfillable space.”[xx]

Further Reading/Viewing:

Hans Christensen – 2011 RIT Innovation Hall of Fame. 10 June 2011.

https://video.wgbh.org/video/antiques-roadshow-appraisal-1979-hans-christian-sterling-silver-bowl/

Oral History Interview with Hans Christensen. Smithsonian Archives of American Art. 11 December 1981 and 3 December 1982.

Notes: