During Japan’s Edo period (1603–1868), an interesting development occurred that conceivably “sparked” that country’s “love of robotics.”[i] One might wonder what could have such an impact at this juncture in history. Remarkably, it is what the Japanese call karakuri ningyō.[ii] Frequently referred to as the robots of the Edo period, these automata or mechanical puppets became popular mechanisms for amusement, and to entertain at religious festivals, the theater, or even in the home. [iii]

One type of karakuri ningyō is the chahakobi ningyō or tea serving doll.[iv] These semi-humanoid creations stood about twelve inches tall and were typically handcrafted out of wood, including their head and hands which were meticulously carved. They wore elaborate kimonos made of richly adorned fabrics and could have beautifully painted faces and attached hair. In essence, the chahakobi ningyō “mirrored human beings” and functioned as “social communication devices.”[v] When used in the home, they had the ability to “bring people together” and “create dialogue.”[vi]

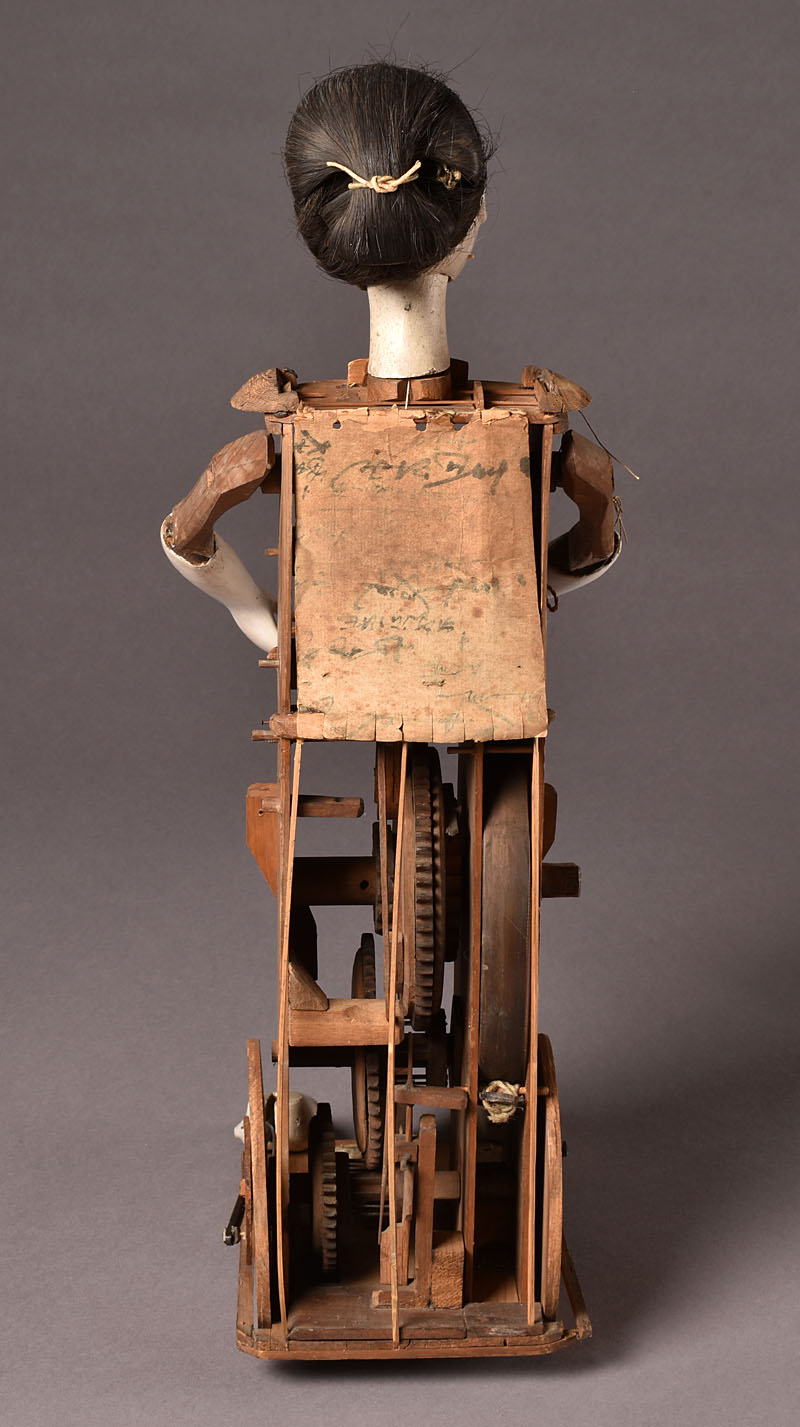

Hidden beneath the striking exterior of the chahakobi ningyō was a “complicated gearbox system” that resembled the innerworkings of a clock.[vii] Essentially, the chahakobi ningyō traveled on “three wheels which were connected to a coiled whale-baleen spring.”[viii] To activate the mechanism a winding key was utilized. Once fully wound up, the doll could carry a cup of tea on a tray across a table to a house guest. When the teacup was removed from the tray, the doll’s arms would rise stopping any movement. After the cup was returned to the tray, the chahakobi ningyō proceeded back to its initial location. As the doll moved, its head sometimes nodded gently.

The first examples of chahakobi ningyō have been traced back to the seventeenth century watch-maker Takeda Kiyofusa.[ix] “The techniques he and his contemporaries used were closely guarded secrets” which would have only been passed from a master to an apprentice.[x] In 1796 this time-honored tradition was forever altered. That year an illustrated anthology of mechanical techniques for Japanese clocks and automata was published. Called Karakuri zui, it was compiled by the skilled engineer and inventor Hosokawa Hanzō Yorinao (c.1741-1796).[xi] This three-volume text, which featured the tea serving doll, is credited as being the “impetus for the popularization of mechanical devices during the Edo period.”[xii] Furthermore, it seemingly allowed for more accessibility to karakuri ningyō “across every layer of Edo society.”[xiii] One craftsmen who credited Karakuri zui as a source of inspiration was Hisashige Tanaka (1799-1881).[xiv] Known as the “Thomas Edison in the East,” he created chahakobi ningyō and invented devices such as the arrow shooting boy or yumihiki-doji.[xv] Karakuri zui, which was translated into English in 2012 by Kazuo Murakami, continues to be an important resource today.

The doll was restored by automaton expert Michael Start, who stabilized the fragile object with cleaning and repairs. He also remade some missing elements, such as the serving tray, winding key (not pictured) and eyes. The missing escapement within the mechanism was not replaced as its design was unknown.

KAMM COLLECTION

The chahakobi ningyō in the Kamm Collection is a sizeable nineteen inches high. The doll is primarily made of wood. However, the pivoting pin-jointed head is paper-mâché, the main spring is whalebone, a back panel is composed of heavy-duty paper, and it has hair that is attached and arranged in a top bun. In addition, the doll had glass eyes which have been restored. The inclusion of glass eyes provides some clues to when it was created. This was a popular trend in the late Edo period but could also be seen in the early Meiji era (1868-1912). After acquiring this tea serving doll, the Kamm Collection received some feedback from experts in the field. It was determined that this chahakobi ningyō is very rare. There are no known comparable examples, and the internal mechanism seems to be more complicated than the versions featured in Karakuri zui.

An interesting aspect of this doll is that its head is paper-mâché with a Gofun finish.[xvi] Since the head was not carved out of wood, this might mean that this chahakobi ningyō was mass produced or perhaps more than one person contributed to its construction.[xvii] Conversely, it has also been suggested that this is “a sign of quality.”[xviii] Upon inspection of the inside of the doll’s head and back, Japanese writing was discovered. The hope was that perhaps these markings would reveal the maker’s signature. However, this turned out to be inconsequential writing on the wastepaper that was used to reinforce the structure. At this point in time, the maker of this chahakobi ningyō in the Kamm Collection continues to be unknown.

This tea serving doll has undergone a conservative restoration with no conjectural additions to its mechanism. Some of its parts have unfortunately been lost to time such as its clothing and numerous elements needed for operation. It was thought best to leave this chahakobi ningyō in its current state, especially since there is no point of reference in the Karakuri zui for the internal mechanisms. This means it is inoperable. However, this automaton in the Kamm Collection still has an arresting presence and speaks volumes about a tradition that ultimately led to some of “today’s cutting-edge technologies.”[xix]

Further Reading/Viewing:

Start, Michael. Secrets of Automata, Ingenious Designs for Mechanical Life. Ramsbury, England: The Crownwood Press, 2023.

Hillier, Mary. Automata & Mechanical Toys: An Illustrated History. London: Bloomsbury Books, 1976.

Hosokawa Hanzō. Japanese Automata: Karakuri Zui: An Eighteenth-Century Japanese Manual of Automatic Mechanical Devices. (Translated by Kazuo Murakami, Murakami Kazuo, 2012.)

Tea Serving Doll – Karakuri Ningyo Video

Hisashige Tanaka Mr. Mechanical Video

Notes: