These two works of art were both acquired from the estate of the influential art critic, historian, and collector Henry Geldzahler (1935-1994).

Geldzahler began his career as a student in the Harvard Fine Arts Department, but left before completing his doctorate to become a curatorial assistant at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 1960, where he eventually oversaw the creation of the 20th-century art department. Geldzahler also served as the New York City Commissioner of Cultural Affairs from 1977 to 1982, during which time he nearly doubled the budget of the department. He was an early supporter of the Pop Art movement, and friends with many of the artists he wrote about.

The earlier of these two works, Teapot (ca. 1888) is a ceramic sculpture by the French artist Jean-Joseph Carriès. Notably, this piece is not a functional teapot, but, instead, a sculpture in the form of a teapot, with a lid-shaped protrusion that cannot actually be removed.

Carriès began his education as an apprentice to a sculptor of religious images. He briefly studied as a probationary student at the Ecole des Beaux–Arts in Paris, but failed his admissions exam. He entered his first work in the Salon in 1875, but did not become well-known until 1882 when his work was featured in a private show by the Cercle des Arts Libéraux. For much of his career, Carriès made portrait busts and imaginative sculptures of animals and mythological creatures. These sculptures were usually from plaster coated in bronze or ceramic. Later in his career, Carriès experimented extensively with ceramic materials and made functional pottery in a Japanese-inspired style that was popular in France at the time.

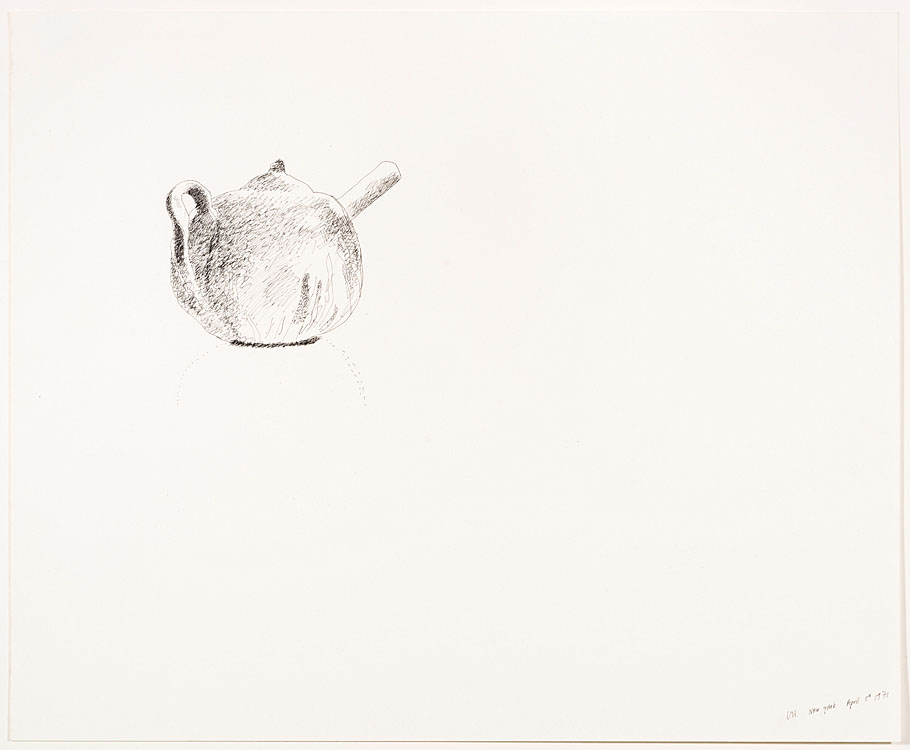

The second of these works is an untitled ink drawing (1971) by the English artist David Hockney, which depicts Carriès’s Teapot. Over the span of his career, Hockney worked in many styles of art and in many media, including drawing, painting, and photography. For much of the 1960s and 70s, Hockney lived in the United States and taught at a series of American universities. During this time, from 1964 to 1967, Hockney created his iconic California series, which featured recurring motifs of modernist architecture and furniture, swimming pools and other man-made water features, and a mix of chiaroscuro shading with stylized reflective surfaces. In these paintings, Hockney often depicted his friends and art collectors that he knew, as well as sculptures and paintings owned by the people in the paintings.

In the late 1960s, Hockney began to shift to a more naturalistic style, but continued to create portraits of friends and fan, including several portraits of his friend, Henry Geldzahler. These include the painting Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott (1969) and ink drawing Portrait of Henry Geldzahler (1973).

This drawing of Carriès’ Teapot was likely created during the time Geldzahler owned the sculpture. This work includes several common elements from in Hockney’s work at the time, including the mix of realistic shading in the teapot body and the highly stylized depiction of its shadow below, as well as the posing of the sculpture to show less than the widest surface area, which Hockney did in many of his figurative works.

In his book on the Kamm Teapot collection, The Artful Teapot, art historian Garth Clark also argues that this drawing can be seen as a symbolic portrait of Henry Geldzahler himself. Clark also calls this drawing “an imaginary personal diary” of the history of this teapot and its owner. In Geldzahler’s 1977 essay on Hockney’s work, Geldzahler mentions that Hockney would often do line drawings in rapidograph technical pens as a way of taking notes for future projects; this drawing may be one such note for future paintings.

Further reading:

Chilvers, Ian. “Hockney, David” The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford University Press.

Clark, Garth. “Introduction: Tea, Blood, and Opium: A Brief History.” The Artful Teapot. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2001. 11-27.

—. “Biographies.” The Artful Teapot. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2001. 218-251.

de Margerie, Laure. “Carriès, Jean.” French Sculpture Center. frenchsculpture.org, funded by the University of Texas at Dallas, the Nasher Sculpture Center, the Institut national d’histoire de l’art, the Musée d’Orsay, the Musée Rodin, and the Ecole du Louvre.

Geldzahler, Henry. “David Hockney [1977].” Making it New: Essays, Interviews, and Talks. Harcourt, 1996. 126-153.

Goldberger, Paul. “Henry Geldzahler, 59, Critic, Public Official and Contemporary Art’s Champion, is Dead.“The New York Times 08-17 1994.

“Hockney, David.” Benezit Dictionary of Artists. Oxford Art Online.

Janoray, Charles. Symbolism and the Grotesque: The Fantastical Creatures of Carriès and Ringel D’Illzach. New York: Charles Janoray LLC, 2006.

Livingstone, Marco. “Hockney, David.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online.

Tate Museum. “David Hockney born 1937.” The Tate Museum.

Thiebaut, Philippe. “Jean Carriès.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online.

Weinberg, Jonathan. “Farewell Henry: Henry Geldzahler 1935-1994.” Provincetown Arts 1995: 60-1.

Save

Save

Save

Save