This blog post concentrates on another prevalent theme within the Kamm Teapot Collection, art influenced by industry. These objects contain recognizable industrial references such as smokestacks as well as man-made mechanisms and hardware like engines, screws, and bolts. Many of these works utilize the illusionistic trompe l’oeil technique to realistically imitate other materials in clay.[i] This is seen in the teapots of Susan Beiner, Joshua Foy, Paveen “Beer” Chunhaswasdikul, and Andrew Massey. For this post, we will focus on Jason Walker and Steven Montgomery who are known for their industrial inspired creations that, at times, also fool the eye.

Jason Walker (b. 1973)

Jason Walker’s ceramic work explores the relationship between nature and industry or technology.[ii] He juxtaposes “light bulbs, plugs, powerlines, and pipes with birds, insects, and organic matter such as leaves and trees.”[iii] This striking mixture of biological components and man-made mechanisms is skillfully presented in a “seamless combination of sculpture and painting, form and decoration.”[iv]

Walker was born and raised in Pocatello, Idaho. Growing up he spent a great deal of time outdoors, hiking, backpacking, and cross-country skiing.[v] However, during his childhood, Walker was also exposed to his father’s work at the Idaho National Laboratory which engaged in the “construction, testing, and opera[tion] of nuclear reactors.”[vi] These two different worlds most likely laid the foundation for his later explorations of nature and technology in clay.

Walker majored in illustration at Utah State University in Logan and received a M.F.A. in ceramics from Pennsylvania State University in State College.[vii] Following graduate school, he taught at Napa Valley College in Northern California. It was here, living near the grossly polluted Napa River and the Silicon Valley, that Walker’s “ideas coalesced.”[viii] He began contemplating the relationship between nature and technology. Then, in 2002, he received a fellowship from the Archie Bray Foundation in Helena, Montana. This fellowship “was a major turning point.”[ix] Walker says, “at the Bray, it all came together.”[x] It allowed him “the opportunity to focus on his work” and it “gave him national exposure.”[xi] Ultimately, Walker started considering topics such as the future of the planet and man’s effect on it as well as “how technology has influenced and molded our perceptions of nature.”[xii]

Within the Kamm Collection there are seven works by Walker. Most of these porcelain teapots contain intricate black underglaze drawings and a selective use color. Among this striking group, the teapot sculpture called The Ball and Chain of Civilization stands out. Here Walker depicts two scenes in blue on the form’s rounded body: a cityscape and a rural landscape. These depictions are surrounded by industrial and mechanical components. The teapot rests on a stand that is modeled to look like a bicycle gear sprocket and chain rim. Shaded pipe-like tubes form the handle, spout, and fixture for a flame finial. Also, extending from below the handle is a realistic and hefty-looking ball and chain. With works such as The Ball and Chain of Civilization, Walker believes that he can “attempt to portray nature’s vastness and human-kind as a small proponent of it…[he] draw[s] the small things of nature big and the huge creations of man small. [He] want[s] to show how we influence the landscape, or nature.”[xiii]

Walker currently lives in Cedar City, Utah and teaches full-time at Southern Utah University. In order to recharge creatively he does urban expeditions to explore “the landscape of technology” as well as “image collection research excursions” to places such as Yosemite National Park.[xiv] Opening January 24, 2020, Walker’s ceramic work will be included in the exhibition ABOUT FACE: Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture at the Art Museum of South Texas in Corpus Christi.

STEVEN MONTGOMERY (B. 1954)

Steven Montgomery is best known for his large-scale ceramic work inspired by industrial objects or mechanical equipment. The New York art critic Robert C. Morgan has described Montgomery’s sculpture as “synthetic engines” that tell “the story of an era in transition between industry and post-industry, between hard material and soft, between the legacy of work and the vestiges of frustration.”[xv]

Montgomery grew up on the northwest side of America’s motor city, Detroit, Michigan. As a child he says, “rusted junk and industrial debris were commonplace. A charred car blocking a side street was really not much of a surprise.”[xvi] These surroundings certainly had an impact on him, and Montgomery’s work reflects “[his] affinity for the aesthetics of damage, destruction, and any evidence of the passage of time.”[xvii] He received his bachelor’s degree at Grand Valley State University in Allendale, Michigan and in 1978, he obtained an M.F.A. from the Tyler School of Art of Temple University in Philadelphia.[xviii] At Tyler, Montgomery studied with Rudolph Staffel who is widely recognized for his innovations with porcelain.

In the early 1980s he moved to New York City. After arriving Montgomery says “[he] made the decision to radically reverse course and abandon clay completely…[he] spent about five years deeply immersed in experimentation, largely working with metal, found objects, and a great deal of drawing and painting.”[xix] This decision allowed Montgomery time to mature as an artist. When he did return “home” to clay it was “with an entirely fresh perspective.”[xx]

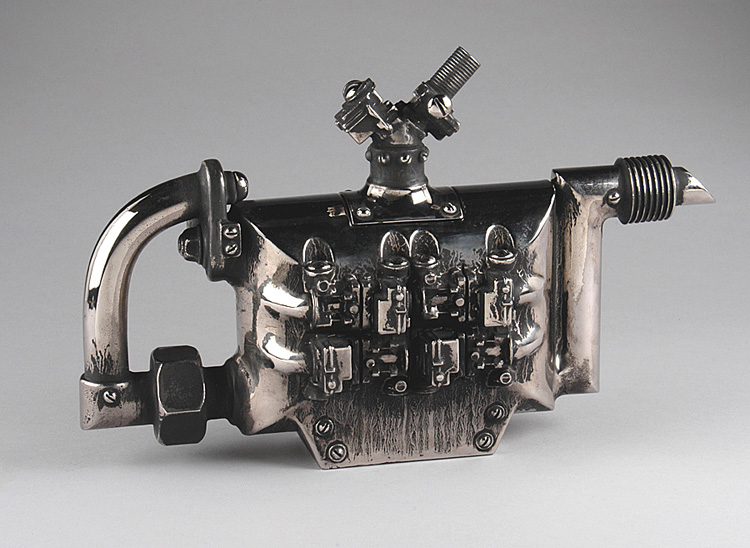

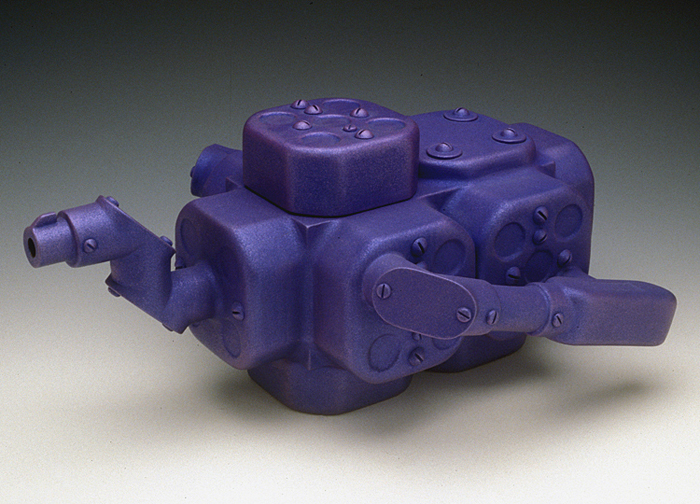

There are seventeen of Montgomery’s ceramic works in the Kamm Collection. These designs contain a range of industrial and mechanical components such as engine blocks, copper piping, electrical junction boxes, wrenches, pipes, and screws. In some instances, the surfaces have corroded sections or incorporate matte industrial-like colors. In one teapot, called Device, Montgomery covers the rectangular clay form with a silver luster glaze and blackened crevices. High relief mechanical shapes cover both sides of its body. The spout and opposing curved handle realistically resemble pipes, nuts, and slotted screws. Decorating the lid is a Y-angled threaded rod and other mechanical accents. Through his work Montgomery hopes to communicate the connections between humans and machines. He points out that “machines are an extension of human power” and “they are also subject to frailties, flaws, foibles, and the ravages of time comparable to that of those who create them.”[xxi]

Montgomery currently has a studio in Williamsburg, Brooklyn and teaches at Hunter College in Manhattan. For inspiration he does “photographic reconnaissance missions out into the industrial landscape.”[xxii] Montgomery says, “like a landscape painter, my observations of what I see around me are critical. However, my process is intuitive, impulsive, chaotic, and only after the dust settles do I have a clear sense of what I am about.”[xxiii]

Further Reading/Viewing:

Clark, Garth. The Artful Teapot. London: Thames & Hudson, 2001.

Trompe l’oeil: Levine, Shaw, Leon. Kamm Teapot Foundation. 30 May 2019.

Walker, Jason and Stefano Catalani. Jason Walker: On the River, Down the Road. Bellevue, Washington: Bellevue Arts Museum, 2014.

Notes: