“[Karen Karnes] was a towering figure of the postwar studio pottery movement, pioneering salt-glazing in the 1960s and wood-firing in the 1980s. Her work opened undreamed of possibilities of expression for the handmade pot. For the many potters who knew her, she was a mentor whose work embodied the creative power and singular voice to which we all aspire—her life in complete harmony with her creative vision.”[i]– Mark Shapiro, 2016.

Foundations

Beloved studio potter Karen Karnes (American, 1925-2016) spent her early years in the New York City area. Her parents were Jewish garment factory workers who had immigrated to this country as teenagers.[ii] They were also socialists actively involved in the labor movement. Initially Karnes and her family lived in a “cooperative colony,” or housing project, specifically designed for working class people in the Bronx.[iii] This community, which was the first of this type in the country, was very left wing politically. Karnes considered it a “social experiment” not only architecturally, but “culturally with its own library, art classes, and Yiddish-language school.”[iv] This unique environment proved to be a wonderful place to grow up. With her parents working, Karnes was given a great deal of freedom and developed a strong sense of independence.

Karnes decided on her own that she would attend the High School of Music and Art in Manhattan and later, she enrolled at Brooklyn College where she studied under the architect Serge Chermayeff.[v] Chermayeff, who would become her mentor, had set up a Bauhaus type design program in which Karnes excelled. “[She] loved the Bauhaus approach – [she] had suddenly found a kind of art instruction compatible to [her].” In the summer of 1947 Karnes received additional Bauhaus training at the experimental and highly influential Black Mountain College in North Carolina. There, she took a class under the prominent artist and teacher Josef Albers who she has amusingly described as “hard clay not soft clay.”[vi]

Discovering Clay

While at Brooklyn College, Karnes also met fellow art student David Weinrib whom she married after receiving her bachelors.[vii] It was Weinrib who introduced her to ceramics. One afternoon he brought home a lump of clay for her to experiment with out on their deck. This initial encounter was “miraculous.”[viii] “[She] had found [her] material.”[ix] Prior to this, Karnes had no experience with ceramics. Therefore, these early works were hand built or created using a press mold because she did not know how to throw on a wheel.[x]

In 1949 Karnes and Weinrib moved to Sesto Fiorentino, Italy. While they were in Italy, she continued working in clay. Karnes experimented a great deal, especially with texture, and learned to throw on a wheel by observing classes at a local school. Soon she had set up a studio space in their apartment. Her pottery, even at this early point in her career, must have been noteworthy. After meeting the architect and industrial designer Gio Ponti, he decided to publish examples of Karnes’ work in his magazine Domus.

Karnes and Weinrib returned to the United States in 1951 and she began a fellowship at Alfred University.[xi] There, she worked independently under the direction of professor Charles Harder. From this experience Karnes said she wanted “to learn what [she] didn’t know – how to fire a kiln, how to make a glaze – all the basics of making pots.”[xii] She was determined to be a full-time potter even though “[she] didn’t see other people doing it…[xiii]”

Black Mountain College

In the summer of 1952 Karnes and Weinrib eagerly accepted the position of potters-in-residence at Black Mountain College. The couple were given “a little money, a studio to work in, and a place to live – all [they] ever wanted.”[xiv] They arrived at just the “right moment” before the school “imploded” from financial strain.[xv]

During Karnes and Weinrib’s time at Black Mountain the college hosted some important workshops.[xvi] The first of which proved to be very influential for Karnes. In October of 1952, the renowned potters Bernard Leach and Shoji Hamada visited the school. They were accompanied by the philosopher Soetsu Yanagi and the ceramist Marguerite Wildenhain who acted as “mistress of ceremonies for the occasion.”[xvii] During this two-week long event, it was Hamada that made a life-long impression on Karnes. He had a “quiet presence” and was completely “attuned to his own impulses, unbothered by his surroundings or the expectations of his audience.”[xviii] Hamada “just accept[ed] the clay and the wheel as they [were] and [did] the best [he] could with what [he had].”[xix] By watching him work, Karnes discovered her “own creative center” which forever changed her mindset in the studio.[xx]

At Black Mountain Karnes primarily worked on the wheel producing functional pottery which she sold through the Southern Highland Craft Guild. The Kamm Foundation has a glazed stoneware coffee set in its collection which was reportedly made while she was at the school. Like other examples from this period, these forms have a “crisp strength and undercurrent of lyricism in the throwing.”[xxi] The Kamm Collection’s set includes a coffee pot, sugar bowl, creamer, and six cups with saucers. Each of these simple, but elegant designs are a light gray color except when the rust brown clay body peeks through the glaze.

Gate Hill Community

After two years at Black Mountain, Karnes and Weinrib were invited to join a group of artists who were forming an idealistic cooperative in Stony Point, New York. Together they wanted to create a respectful place where artists could work and “everybody took care of everybody else.”[xxii] Called Gate Hill or “The Land” by its occupants, this community picked up where Black Mountain left off. Gate Hill’s founding members Paul and Vera Williams, John Cage, Mary Caroline (M.C.) Richards, and David Tudor were all friends at the college.[xxiii]

Gate Hill would become Karnes’ home for the next twenty-five years. She remained even after Weinrib departed and raised their son within this supportive environment. In essence, at Gate Hill she could live the “life…[she] loved.”[xxiv] However, it must be stressed that Karnes always “pursued her own distinctive path in clay.”[xxv] While she might have lived in an artist colony, she maintained her independence in the studio as well as a strong “stylistic compass.”[xxvi] Even when Karnes encountered individuals who profoundly transformed the field of ceramics, she remained steady in her convictions. It was “the character of the clay that motivated her consistently – how it handled, how it responded to different methods of firing and glazing,”[xxvii] At Gate Hill Karnes produced a wealth of pottery. These works include her popular oven top casseroles using a flameproof clay body and her masterful salt-glazed forms which garnered widespread attention for their “perfect union of form, surface, and aesthetic sensibility.”[xxviii]

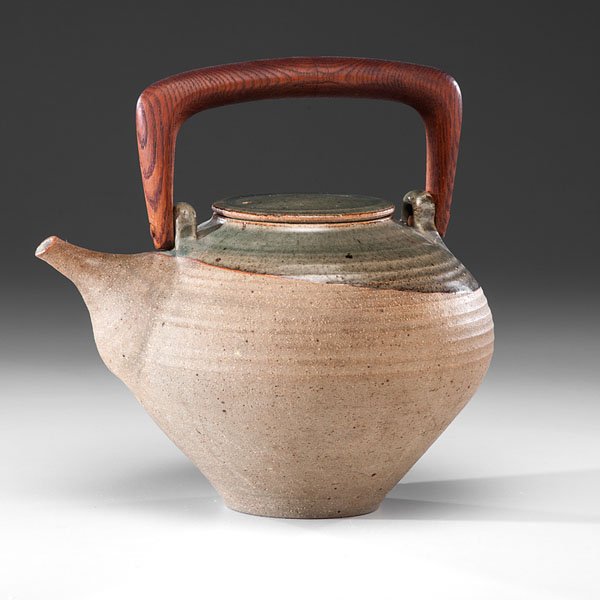

Karnes’ “commitment to clay deepened” during her years at Gate Hill.[xxix] In addition to her functional pottery she created some larger scale objects as well as some interesting sculptural work. The Kamm Collection has two stoneware designs from this period: a large bulbous teapot and a collapsed coffee pot. The mostly unglazed teapot has a wooden handle and a swath of glossy gray-green glaze across its top. With its soft lines and balanced proportions, the vessel feels both modest and sophisticated. The other work, called Shelf Edge Coffee Pot, shows another side of Karnes’ artistry.[xxx] The wheel-thrown brown glazed form reveals a spontaneous moment frozen in time. It appears caught in a collapsed state on the brink of falling off the edge of its platform. A similar work by Karnes was included in a 1966 exhibition entitled The Object Transformed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This example features an arrangement of deformed ceramic pitchers leaning against one another. Like the coffee pot they were once functional, but now in their altered condition these pitchers present a visually compelling sculpture.

Following Gate Hill

Karnes left Gate Hill in 1979 and moved to Vermont with her partner British artist Ann Stannard. The two had met when Stannard came to the United States to do a kiln building workshop. In Vermont Karnes switched her focus from salt wares to wood-fired vessels. This was a “risky decision” since she had developed a reputation as “the most significant salt-glaze practitioner in America.”[xxxi] However, her wood-fired work would also explore new frontiers and “reinvent the tradition.”[xxxii] Unfortunately, in May of 1998 a fire destroyed Karnes’ Vermont home and studio, but with the support of the ceramics community she rebuilt. Following this tragedy, she took “greater risks.”[xxxiii] The fire seemed to give Karnes “a better understanding of her legacy and its value.”[xxxiv]

Further Reading/Viewing:

Clark, Garth. Karen Karnes. New York, NY: Garth Clark Gallery, 2003.

Galusha, Emily and Mary Ann Nord, eds. Clay Talks: Reflections by American Master Ceramists. Minneapolis, MN: Northern Clay Center, 2004.

How to Craft a Revolution (with guidance from Karen Karnes). Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center. 7 September 2020.

Mark Shapiro: The Ceramic Art of Karen Karnes. American Craft Council. 24 May 2012.

Masterpieces at Midday: Karen Karnes, Transcending Form with Flame. ASU Art Museum. 30 November 2020.

Oral History Interview with Karen Karnes. Conducted by Mark Shapiro. Smithsonian Archives of American Art. 9-10 August 2005.

Shapiro, Mark, ed. A Chosen Path: The Ceramic Art of Karen Karnes. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Notes: