The artist Kevin O’Dwyer (American/Irish, b. 1953) has received international recognition for his work which ranges from holloware and jewelry to photography and large-scale outdoor sculpture. These creations reflect not only his keen interest in modern architecture, but also a fascination with antiquity. For over forty years, O’Dwyer has made “art that is as structural as it is organic, both solid and fanciful, sprinkled with imagination and a dash of hard-edge design.”[i] It is very clear that this is a skilled individual who mastered his craft. Each design is “timeless, thought provoking, and responsive to the human spirit.”[ii]

The Kamm Collection has one work by O’Dwyer called Rocking Teapot (1995). He also worked with the Kamm Teapot Foundation in 2007 to catalog and document its metal collection. The following interview was conducted via email in January and February of 2023.

Allie Farlowe: You were born in Lindenhurst, New York, but your family relocated to Ireland where you attended secondary school and then studied biochemistry at the Waterford Institute of Technology.[iii] This dual experience in your youth ultimately had a significant impact on your metalwork. Could you share with our readers how your exposure to these two different environments has been influential?

Kevin O’Dwyer: The culture shock of leaving suburban New York in the late ‘60s to live in rural Ireland was like stepping back 30 years in time and provided an opportunity to explore a very different landscape, historical/political context, and education. There is no doubt I would not have considered and eventually decided on a career in the art/craft of silversmithing/metalsmithing/sculpture if we had not moved to Ireland. As a teenager, growing up in Cashel, I was surrounded by some of our most important Irish medieval architecture including the Rock of Cashel (cathedral that I cycled by on the way to school) and numerous monastic ruins that sat in the surrounding fields. Stone buildings over 800 years old with a story to tell. These monuments captured my imagination, and I spent many hours—with camera in hand—exploring the monastic ruins, its wonderful carved stone imagery, and the surrounding landscape.

Although I did not study metalsmithing in Ireland, my deep interest in Irish archaeology led me to our National Archaeology Museum in Dublin, where artefacts from Bronze Age to medieval metalworking collections were prominently displayed. I was fascinated by the imagery and how the wonderful artefacts were made. Finishing secondary school, I had the option to study archaeology, but I wanted to travel, and a science degree was a ticket to greater opportunities in the early ‘70s. I continued to document man’s engagement with his landscape from Neolithic standing stones and burial tombs to monastic sites throughout my college years and beyond. My camera has continued to be an important tool throughout my career, and it would not be until living in Chicago that I had the opportunity to study metalsmithing.

While living in Chicago, you couldn’t but be influenced by the strong architectural forms in the cityscape. Especially the many wonderful architectural gems by Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe (to name a few) as well as the metalsmiths who created decorative works during the Arts and Crafts Movement, Art Nouveau and Art Deco periods. Important references during my time in Chicago, and they were important references for my “architectural series” of vessels that I created throughout my career.

Allie Farlowe: From what I understand you moved to Chicago in 1977 and were working as a biochemist. However, a curiosity about metal soon led to night classes with jeweler Harriet Dreissigger and eventually an apprenticeship with master silversmith William Frederick. Can you describe the work you were creating in Dreissigger’s classes? Also, how was your apprenticeship structured and what do you think is the most significant thing you learned from Frederick?

Kevin O’Dwyer: I eventually arrived in Chicago via London and New York. Although working in the food science industry, my passion/hobby was photography and archaeology. My interest in medieval metalsmithing, especially the techniques of repoussé and enameling, propelled me to find a night class to explore the craft. Harriet Dreissigger was recommended to me for study as she was a jeweller and enamellist who had studied with John Paul Miller at the Cleveland Institute of Art. I started night classes with Harriet, and I started work on large copper panels using the repoussé technique. As I became more comfortable with metalsmithing tools, torches, etc., I studied enamelling, jewellery making and some small silversmithing projects during the classes.

I studied with Harriet one night a week, then two nights a week. I eventually set up a small metalsmithing studio of my own to continue the work at home. Eventually I packed in the day job, worked a couple of days a week for Harriet, studied at the Art Institute (SAIC, with Bill Brincka, sculpture department) and eventually had the opportunity to apprentice with master metalsmith Bill Frederick. My apprenticeship with Bill was over 2 ½ years (1981-1984). I truly learned the art of metalsmithing from Bill. From initial design development and layout to the various construction techniques—raising, forging, forming, and the finishing of functional holloware. During my apprentice I had the opportunity to work with Bill on commissions as well as make my own pieces. Bill Frederick was part of the lineage of the Kalo Shop. A group of Scandinavian metalsmiths who arrived in Chicago early in the 20th century worked for Clara Barck Welles who founded the Kalo Shop. Bill studied with and worked for their master metalsmith Daniel Pederson. When the Kalo Shop disbanded in the late ‘50s, Bill inherited all the metalsmithing tools! Bill was Pederson’s last student/apprentice, and I was Bill’s last student/apprentice.

Bill Frederick and Harriet Dreissigger were both wonderful, patient teachers who supported my passion. I kept in constant contact with Harriet and Bill until they sadly passed away. I was asked to document and disband Bill’s workshop when he passed away. We were able to donate his incredible archives and tools to the Chicago Historical Museum. His archives are online. Bill often talked about the “significant others” in a career—those who have a lasting influence on your path. Harriet, Bill and Heikki were my “significant others” in metalsmithing.

Allie Farlowe: You also studied with the influential Finnish American silversmith Heikki Seppä who is known for his technical and sculptural contributions to the field of metalwork in the United States. From Seppä you learned anticlastic raising and reticulation. Can you talk a little about this experience and the works you have created utilizing these techniques?

Kevin O’Dwyer: I first met Heikki at Washington University (St Louis) when I was visiting his metalsmithing studio. I was very interested in the flowing sculptural forms Heikki and his students were creating as I felt they referenced the flowing lines of Irish Neolithic and medieval artefacts. Heikki invited me to take one of his workshops. The opportunity to explore metalsmithing purely as a sculptural form, as opposed to a functional form, was very exciting and liberating. I had the opportunity to study with Heikki on several occasions before I moved back to Ireland. I have used the technique of anticlastic raising combined with traditional metalsmithing techniques throughout my career. The spiculum forms on my teapots were developed during my studies with Heikki.

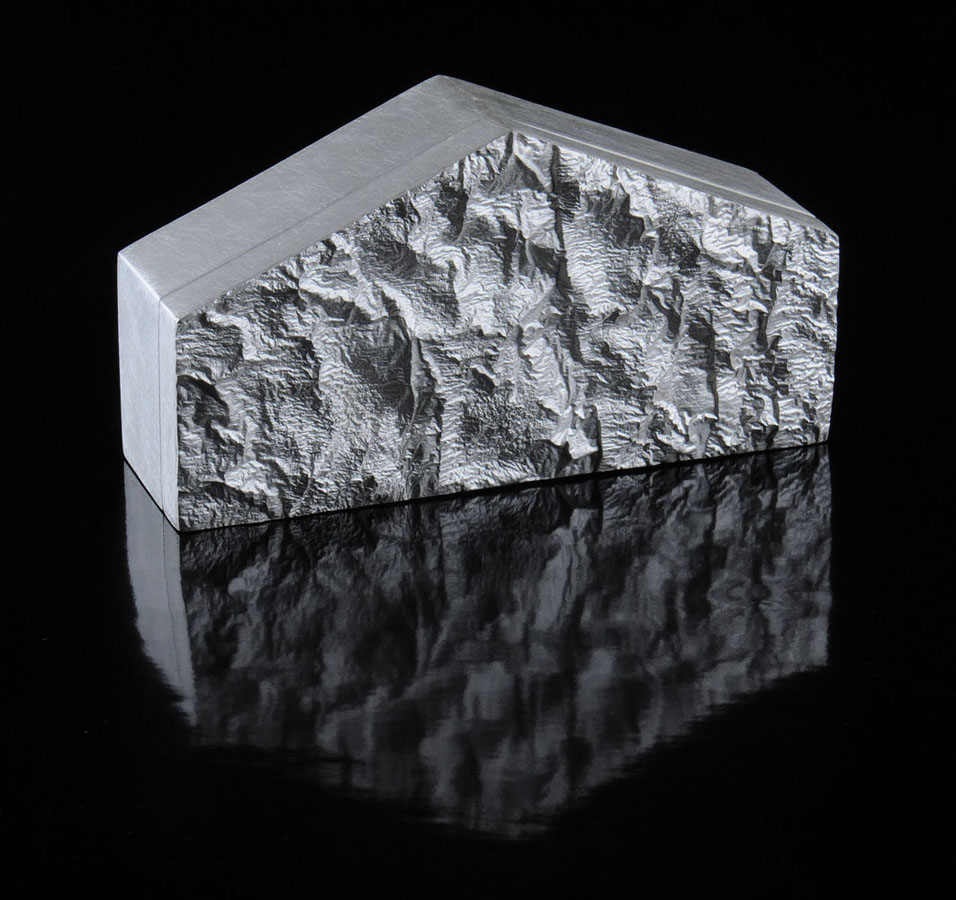

Reticulation was a technique that Heikki brought to the United States from his study and apprenticeship in Finland and Denmark. Heikki said it was a technique developed by the Fabergé workshops. Heikki learned the technique in the Georg Jensen studios from a metalsmith who had worked for Fabergé. Heikki shared the technique with his students, and I have continued to develop the process and use it on my holloware pieces providing wonderful spontaneous textured surfaces that work with my architectural forms—like cuts in the landscape.

Heikki and I became fast friends. When I returned to Ireland to set up my studio, we continued corresponding via letter writing. At some point Heikki had retired and moved to Washington state. I had moved my studio from Dublin to a rural setting along the Silver River. We both loved gardening so many of our letters were about our gardens! Again, he was very supportive and a strong influence.

To return to the topic of reticulation, it relates to my use of textured surfaces. I loved the contrast between the textured and the high polished. It probably first dates back to the planished surfaces on functional holloware combined with high polished or patinaed surfaces to create contrast. Bill Frederick was always playing with different surfaces on his holloware as well as combining alternative materials. My contemporary take on this combination was inspired by the Memphis style—Italian designers having fun with textures in the ‘80s. The Victoria and Albert Museum has a vessel of mine that combined the textured body with high polished handle in their “postmodern” collection.

I researched Victorian/Edwardian silver engraved trays in Birmingham, England (at one time the largest manufacturer of silver and silverplate articles in the world) that were roller-printed using engraved steel plates and large rolling mills. I worked with a steel engraver to develop some plates from my designs. The steel plates were sandwiched with sterling silver and put through a large industrial rolling mill. The textured silver sheets were then cut and fabricated. The Rocking Teapot 1999 (pictured above) was one of the patterns.

I also used etched patterns for some of my pieces in later years. Again I used a Birmingham company that specialised in etched computer boards but was capable of etching large sheets of silver. A nice deep etch to play with.

After my solo exhibition at Artizana Gallery in Manchester (early ‘90s), I was contacted and collaborated with a representative of Alessi in England to do some development work on manufacturing textures for production.

Allie Farlowe: In 1987 you returned to Ireland where you continue to have your studio. However, you have remained active in the United States exhibiting, giving lectures, teaching workshops, and even serving as an art administrator. This gives you a unique perspective. Are there any striking differences between the American and European approaches to silversmithing/metalsmithing? This could extend beyond the making of objects to the presentation and marketing of those objects.

Kevin O’Dwyer: I have been fortunate to have the best of both worlds over my career! I continued to exhibit in the United States through exhibitions and galleries. I was fortunate to have my work represented at SOFA Chicago and SOFA New York over a 12-year period. And in public collections both in Europe and the United States.

In my opinion, the European tradition of metalsmithing was more focused on the functional object, be it for presentation or home use until late in the 20th century. When I was exhibiting at Goldsmiths Hall (London) in the late 1990s–early 2000s, the silverware on exhibit was well designed functional artefacts for home and ceremonial use. The American tradition, especially in the university metalsmithing departments, was more explorative and the focus was not limited to the functional. There was a strong sculptural aesthetic. The downside of this (as observed from teaching workshops in the USA) was that students did not spend as much time developing some basic metalsmithing techniques. I observed some wonderful student concepts that suffered from poor construction, making and finishing techniques.

I personally would say my work has been influenced from where and who I studied with. Although both Bill and Heikki came from a Scandinavian design and making tradition, they were also innovators and disruptors in their field. Their traditional training provided them with a strong foundation to push the materials they were working with. I was fortunate to receive the traditional metalsmithing training that gave me the ability to push the material into a contemporary/sculptural format as well as creating contemporary functional holloware.

Are there any striking differences beyond the making of objects to the presentation and marketing of those objects? I think social media has become an important tool on both sides of the ocean. Self-promotion provides a small workshop with a way to exhibit their new work at no cost and an opportunity to receive feedback. In recent years I have not been active in exhibiting pieces, but I still upload images onto Facebook and Instagram. From what I have observed, makers in Europe and the USA still seem active in promoting their works at retail, gallery, and wholesale shows.

Allie Farlowe: The work in the Kamm Collection called Rocking Teapot (1995) is part of a larger series. Each of these pieces characteristically feature whimsical sinuous flowing lines that extend outward from an anchoring solid holloware body. Can you talk a little about this series and the inspiration behind these compelling designs?

Kevin O’Dwyer: The development of the teapot series—land and air based!—started when my workshop was in Savannah, Georgia. My wife Adele and myself moved to Savannah (1983-1986) after Chicago. Adele was playing with the Savannah symphony, and I was an artist in education for the Georgia Arts Council. I set up my metalsmithing workshop on Barnard Street. I was making and exhibiting both silverware and jewellery. But, when word got out that a silversmith was in town, I ended up with quite a bit of silver antique restoration work. The main pieces arriving at my workshop were clients’ family silver tea and coffee services that dated back to the turn of the century. After restoration, the owners would never use the pieces except for display! So, I started playing with the concept of using the teapot in a sculptural format as opposed to a functional object. The concept developed over a couple of years combining the sinuous flowing handles inspired by the flowing lines of early Irish metalwork and the Art Nouveau style with a holloware body that referenced a more architectural/Art Deco form. The early teapots were often described as Art Deco meets Art Nouveau. The first series of teapots exhibited were made in my Dublin studio and were featured at the Irish Silver of the ‘90s exhibition. The Ulster Museum purchased the first of this series. The Schneider Gallery (Chicago) exhibited the series at Chicago International New Art Forms Exposition (later to be called SOFA Chicago in 1994) in 1992 and they sold all the pieces exhibited. I’d love to know who has them!

Having fun with the teapot concept, I continued to develop the work and created the Rocking Teapot series. The first exhibition of the rocking teapots was at my solo exhibition at Artizana Gallery (Manchester) entitled Teapots Off Their Trolley. The teapots were also exhibited at my Ulster Museum (Belfast) solo exhibition, the British Crafts Council exhibition 20th Century Silver, and Goldsmiths Hall exhibition Silver and Tea. Helen Clifford, curator of 20th Century Silver, wrote: “O’Dwyer’s extravagant teapots have the same confident presence as those Rococo examples of eighteenth century that made teatime such a social and cultural focal point.”

The teapots arrived back in the United States for a solo exhibition at the Schneider Gallery. The Rocking Teapot that the Kamm Teapot Collection owns was purchased from the gallery. Pieces from this series are also in the permanent collections of the Racine Art Museum, Dublin Goldsmiths, and the Celestial Seasonings teapot collection.

Teapots and I were having fun in my studio. The next series created were Teapots on the Crest of a Wave and they were exhibited at SOFA Chicago (2000) by the Ferrin Gallery (USA) and the Roger Billcliffe Gallery in Glasgow. One of the series is in the permanent collection of the Racine Art Museum. There are also several in private collections including Fleur and Charles Bresler (The Bresler Collection, Washington DC).

Next were the Mardi Gras teapots that were exhibited in New Orleans and at my Eblana Gallery solo exhibition (Dublin 2008). They are in the collection of the Irish Embassy in Japan and some private collections.

The development of the teapot series over 15 plus years is also the time when we have young children, and the playfulness of the teapot concept is referenced with their growth as well as mine!

Although my sculptural teapots were my performative exhibition pieces, I was also making functional tea and coffee services, candlesticks, presentation pieces, etc. for clients throughout this period. The Irish president Mary Robinson commissioned several State gifts including the Irish inauguration gift to Nelson Mandela.

Allie Farlowe: Would you call Rocking Teapot a sculpture, a teapot, or is it sculptural holloware? These categorizations might not be important to you, but it is interesting to see how artists, particularly members of the metals community, view their work.

Kevin O’Dwyer: I think the early ones would be considered sculptural holloware on the theme of teapots beyond functionality. As mentioned previously, the evolution of my teapots went from the functional to the sculptural for exhibitions, but I still made functional tea and coffee services for clients in Ireland, UK, Sweden, Belgium, and Switzerland.

What’s also interesting is that—when creating the early sculptural teapots—I had no idea that teapot collecting was such a big trend in the United States at that time! When the teapots were first exhibited at Chicago International New Art Forms Exposition and they were all sold I was in shock! The teapots continued their journey being part of exhibitions and collections in Europe, United States and Japan.

Allie Farlowe: In 2007 you received the Irish Crafts Council Research Bursary Award. You used the awarded funds to explore the possibilities of working in silver and glass in combination. From what I understand you did a ten-week artist in residence at Pratt Fine Arts Center in Seattle, Washington developing stand alone and collaborative work. Please tell us about this experience.

Kevin O’Dwyer: My first collaboration with glass was in 1995 when I designed the Eurovision Song Contest trophy. It was a cast glass architectural form in combination with a hand forged sterling silver hyperbolic paraboloid form. I worked with glass maker Jim Griffiths on the project that I had proposed to the Eurovision Song Contest committee. Again, I was playing with architectural and flowing forms. I love the drama and tension that it can create within a piece.

I have always had an interest in combining materials. When I taught design practices (part time) in the craft department (metals, ceramics, and glass) at the National College of Art and Design (Dublin) for ten years, I encouraged my students to explore alternative materials in combination with their preferred craft discipline.

My interest in the combination of silver and glass was heightened when I was asked to create a contemporary work responding to a piece of Victorian glass and silver in the Hunt Museum (Limerick) collection. I created a series of contemporary scent bottles for the exhibition. I wanted to develop the concept further and my proposal for the bursary award was to explore the use of the material in collaboration with hot glass professionals. I worked/collaborated with Andy Shea in 2007–08 on a series of glass and silver scent bottles that were functional as well as sculptural. One of them even had a teapot stopper!

At Pratt Fine Arts Center in Seattle (2010) the work was of larger scale and very focused on the sculptural. The flowing forms created in combination with sterling silver spiculums were part of my Below Sea Level series. The use of colour added another dimension to the development of the work. Working with the glass artists at Pratt opened additional collaborative opportunities. One of the glass/silver pieces made at Pratt was purchased by the National Museum of Ireland.

Allie Farlowe: Let’s talk about Sculpture in the Wild, a sculpture park in Lincoln, Montana’s Blackfoot Valley as well as Sculpture in the Parklands in Lough Boora, County Offaly, Ireland.[iv] You helped establish both and acted as director and curator. It is my understanding that at these two parks symposium artists have created sculpture in response to the surrounding environment. Is this what has made these parks so effective? Also, in your opinion what makes the ideal location for a sculpture park?

Kevin O’Dwyer: Sculpture in the Parklands (renamed Lough Boora Sculpture Park in 2012) was established in 2002 when I collaborated with the industrial landowners Bord na Móna to create significant land art installations on their brownfield site. Bord na Móna harvested peat from the landscape for electricity production. I proposed the concept of a sculpture symposium to the industry using some of their cutaway bog that had been depleted of its peat. I invited seven artists to create significant artworks in response to the unique landscape and industrial heritage of the cutaway bogland and to build an awareness of the arts within the community through public participation and interaction. Twenty-eight artists responded to this concept over the ten years I curated and directed the park (until 2010). Sculptors, composers, writers, and choreographers participated in the residency programme. The park now welcomes 100,000 visitors a year.

In 2014 I established Sculpture in the Wild in collaboration with Lincoln (Montana) knife maker Rick Dunkerely and the local community. The park was established on a brownfield site—an old logging site. I directed and curated the initial sculpture symposium and continued to direct the programme until 2021. Artists were invited to create significant artworks in response to the unique landscape and industrial heritage of the logging industry and to build an awareness of the arts within the community through public participation and engagement. Our education programme has hosted over 3,000 pupils from rural schools in Montana. The park now welcomes 50,000 visitors a year.

Both sculpture parks were established in rural communities where the land was abandoned by their respective industries leaving considerable unemployment. The knock-on effect impacts the whole community from local commerce to education opportunities. My perspective was that there was an opportunity, if the community engaged with it, to create an alternative source of commerce and education through culture, i.e. culture brings commerce. At the same time, we—the artists and community—are celebrating the unique landscape and industrial heritage that built the respective communities.

The development of the parks has also given me, as an artist, the opportunity to respond to the industrial history by using/recycling/re-purposing industrial artefacts. The pieces I have created are simple forms/cuts in the landscape that make the visitor respond to the spaces around the pieces. Symposium artists are story tellers, community activists and for the most part environmentalist. Here is a lovely quote that says much about our work:

“Celebrating the past, including its industrial heritage helps open doors to a discussion about the future. The sculpture park allows for a narrative: This landscape is special! Look at the art it inspires! People from across the globe are coming here to be inspired by this landscape – our natural beauty, the wildlife.”

What makes an ideal location for a sculpture park? I don’t feel it’s about an ideal location—more about a community that embraces the concept. The parks that I collaborated on engaged with the local community. The ownership remains within the community. It was not about a wealthy benefactor deciding to donate a collection of sculptures and drop them into a manicured landscape where the pieces are not inspired by the local landscape, heritage, or community. Although a generous gift from the benefactor and an educational resource—there is no connection.

The sculptor Magdalena Abakanowicz noted: “The sculpture park is very often like a zoological garden, the sculptures, created elsewhere and placed accidentally among flowers and bushes, watch the visitor like animals in their cages.”

The concept that I proposed to the communities was to invite artists to create works of art on site that respond to the environmental and industrial heritage of their community. The pieces created are site specific. The community works and engages with the artists while they are on-site during the residency. This creates a strong bond and lasting friendships. Although the pieces created can be quite abstract, the community can learn/discuss the concept with the artist, which creates a greater understanding of the installation. The use of local materials—often re-purposed—also creates a strong connection.

Allie Farlowe: I am impressed by the diversity of your career. While we have touched upon your work as an arts administrator, the principal focus of this interview has been your metalsmithing. However, you have been involved in many other creative endeavors. Is there a thread that ties all these activities together?

Kevin O’Dwyer: A sense of place! A connection with community and the story they have to tell. As mentioned, previously, my journey from suburban New York to rural Ireland made a lasting impression about place. And I have responded to that sense of place, history, and community wherever I have lived and had the opportunity to respond. My initial creative work, as a teenager, was documenting place using my camera and I have continued this journey.

I have never considered myself an art administrator more as an arts instigator! I work from the bottom up developing the concept and delivering the programme. There is a point—when the project is established—that I step away and let the arts administrators take over!

My work has crossed many creative endeavors over the years. And I have had the pleasure of collaborating with artists, fashion designers, graphic designers, writers, craftspersons, and musicians. These were wonderful opportunities that expanded my world view.

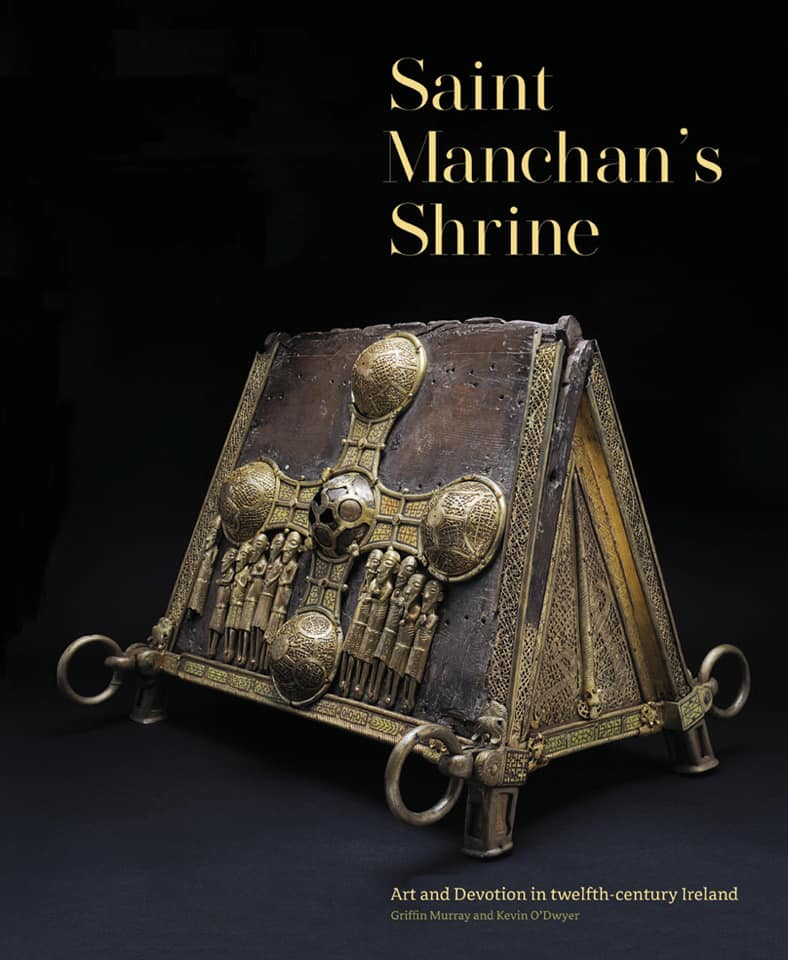

Allie Farlowe: In October of 2022 you released the book Saint Manchan’s Shrine: Art and Devotion in Twelfth Century Ireland. Please tell us a little about this publication and your fascination with this medieval reliquary. From what I understand the shrine has been a point of interest for many years.

Kevin O’Dwyer: The Shrine of Saint Manchan’s is one of the great masterpieces of Irish medieval and European art. My fascination with Saint Manchan’s shrine dates back 40 years! I call the reliquary 300 years of Irish monastic metalsmithing on one box! It combines the 8th–9th century Insular Irish metalsmithing techniques with Hiberno-Urnes and Romanesque metalsmithing and imagery all on one box! It is not only the metalsmithing but the story of a country, a community, and its monastic heritage. Griffin Murray and I examine the history of the shrine and its art and craftsmanship. The book focuses on one artefact and its history over 1000 years.

I had the opportunity to present a paper on the shrine at the 2012 SNAG conference The Heat is On in Phoenix, Arizona. During the preparation for the conference, I photographed the shrine extensively exploring the imagery and the 12th century metalsmithing techniques used to create the reliquary. It was at that time that I was determined to highlight this important piece of metalsmithing in a stand-alone book. I had previously highlighted the reliquary in a coffee table book Stories from a Sacred Landscape[v] that looked at all the monastic sites and artefacts in County Offaly. The shrine and the metalsmiths who created the reliquary deserved a stand-alone publication! It is a beautiful full colour coffee table format publication.

Allie Farlowe: What are you working on now? Do you have any new projects on the horizon?

Kevin O’Dwyer: I will be making and installing a new sculpture at Sculpture in the Wild during September (2023) to celebrate the parks 10th anniversary! I’m very excited to come back to Montana as an “artist” and not juggling the logistics of other artists’ installations and event management!

I am in the middle of a large private sculpture installation made of Corten steel that should be installed by the end of March.

I have been working on a photo-documentation project with my wife Adele who is a musician/composer. We hope to combine an original piece of music (played live) with an image-based walk along the pilgrim’s path (1000 years old walkway) to Clonmacnoise and the River Shannon. Looking at the ordinary and the extraordinary along the way!

I am having fun in the metalsmithing workshop as well, making some work I never got around to, and some pieces I never finished! And then there are the 3-acres of gardens along the Silver River. It keeps me busy and happy!

Allie Farlowe: Thank you for taking the time to discuss your work with the Kamm Teapot Foundation.

Kevin O’Dwyer: Thank you for reaching out. I hope the above makes some kind of sense! So many back stories and so little time.

Further Reading/Viewing:

Grande, John K. “Kevin O’Dwyer: Metal In and Out of Time.” Metalsmith. Vol. 33/No. 1, 2013.

Kevin O’Dwyer’s websites here and here.

Murray, Griffin and Kevin O’Dwyer. Saint Manchan’s Shrine – Art and Devotion in 12th Century Ireland. Offaly, Ireland: Creative Ireland, Offaly County Council Heritage Office, 2022.

O’Dwyer, Kevin. A Sparkling Party – Selected Works in Silver. Dublin, Ireland: Eblana Gallery, 2021.

O’Dwyer, Kevin. Selected Works in Silver 1990-1997. Ulster Museum. 1997.

Saint Manchan’s Shrine. (Lecture about shrine.)

Sculpture installation Na Fánaí Fuachtmhara – The Cold Hills at University College Dublin.

UCD Scholarcast 11: Art and Archaeology: Reflections of an Artist/Curator

Notes: