“For a photographer, light is the real teacher. But it is more than that. Light is the reason for my photographing at all. It is a language that speaks to me. It reveals its subject and becomes an experience that matches my feelings. In that fusion I sense the life force there in the subject and in myself. In that glow, I am in love, madly in love with the world.”[i] – Ruth Bernhard

The celebrated photographer Ruth Bernhard (American, born Germany, 1905-2006) has received widespread attention for her mastery of light and composition. Over the course of her lengthy career, she built “an imposing body of work” that ranged from striking still lifes to dramatic nudes.[ii] Bernhard, who worked almost exclusively in black and white, believed that “the creation of a photograph is experienced as a heightened emotional response, most akin to poetry or music, each image the culmination of a compelling impulse that [she could not] deny.”[iii]

EARLY YEARS

Bernhard’s father was the acclaimed artist and graphic designer Lucian Bernhard who is best known for his contributions to advertising and typeface.[iv] Following in her dad’s footsteps she initially studied art history and typography for two years at Berlin’s Academy of Art. Then in 1927 she moved from Germany to New York City.[v] There, Bernhard briefly worked as a darkroom assistant to photographer Ralph Steiner at The Delineator magazine. She was taught some basics of the business and she watched as he shot images for the publication. However, Bernhard found the job “uninteresting,” and she was ultimately let go.[vi] Following her departure, she ended up using her severance to help a friend in need of money.[vii] In turn he gave Bernhard his camera, a tripod, and some other equipment. Thus, began Bernhard’s career as a freelance photographer.

Bernhard’s first serious photograph was called Lifesavers. The work, which “turns pieces of mass-production candy into a meditation of abstract form,” caught the attention of Dr. M.F. Agha, Vogue magazine’s art director.[viii] He was instrumental in getting the image published in Advertising Arts in 1931. Following this placement, Bernhard received many assignments that ranged from photographing the work of industrial designers Henry Dreyfuss and Russel Wright to taking pictures of the Museum of Modern Art’s 1934 Machine Art exhibition.

In New York Bernhard became very involved with the lesbian sub-culture of the artistic community. It was during this period that she first began photographing women in the nude. Ultimately Bernhard’s dynamic depictions of the female body would become her most notable work. Fellow photographer Ansel Adams asserted that she was in fact “the finest photographer of the nude form.”[ix] Bernhard’s goal with these sensual photos, was “to raise, to elevate, to endorse with timeless reverence the image of [the] woman…”[x]

WESTON AND CALIFORNIA

In 1935 Bernhard met acclaimed photographer Edward Weston during a walk on the beach in Santa Monica, California.[xi] This chance encounter would inevitably transform her entire perception of photography. Bernhard stated, “I was unprepared for the experience of seeing [Weston’s] pictures for the first time. It was overwhelming. It was lightning in the darkness…here before me was indisputable evidence of what was possible – an intensely vital artist whose medium was photography.”[xii] In 1936 Bernhard would move to California in hopes of studying with Weston. They would become lifelong friends. In her later years Bernhard declared, “[Weston] completely understood me. I have had many loves in my life, but I have never had a person in my life whom I loved more than Weston…he was a great soul, a fine artist, and a true mentor.”[xiii]

Bernhard would become associated with an informal group of American West Coast photographers called Group f/64 which included artists such as Weston, Ansel Adams, Minor White, Imogen Cunningham, and Dorothea Lange. These individuals were committed to producing pure photography. In essence, they focused on “the clarity and sharp definition of the unmanipulated image.”[xiv] F/64 was the smallest lens aperture available in large format view cameras which yielded the sharpest depth of field. Their name supported their belief that “photographs should celebrate rather than disguise the medium’s unrivaled capacity to present the world ‘as it is.’”[xv]

Bernhard left California after three years and returned to New York. While living on the East Coast, she received commercial commissions and continued to develop her personal photography. It was during this period that Bernhard met Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz who offered to recommend her for the Guggenheim Fellowship. Eventually her time in New York would end. Bernhard felt an undeniable longing to return to California to be “near Weston in his declining years.”[xvi] She relocated to the Golden State in 1953 and settled in the San Francisco Bay area.[xvii]

KAMM COLLECTION

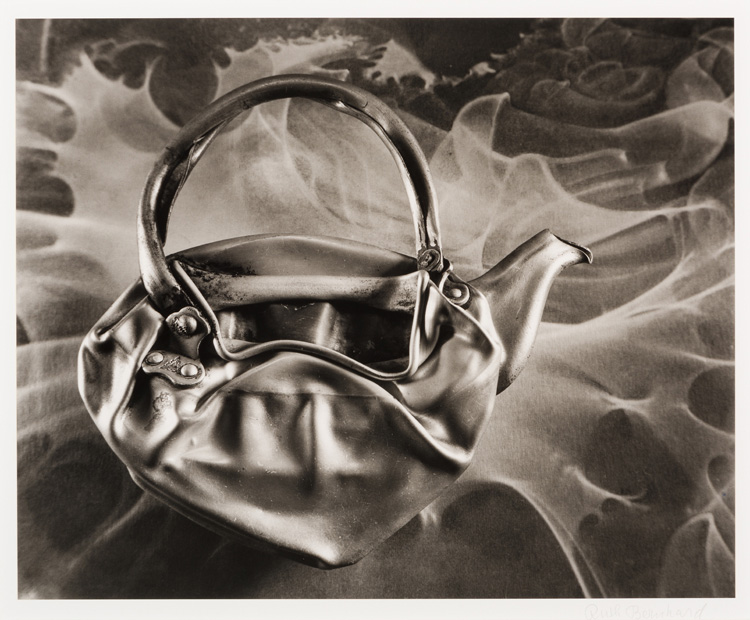

The Kamm Collection has a black and white gelatin silver print called Teapot which was originally taken in 1976. In this surrealistic photograph a flattened metal teapot rests upon what appears to be whitish atmospheric waves. In actuality, the background is simply a poster that featured an enlarged reproduction of a water drop in motion.

Bernhard created numerous photographs that focused on inanimate objects. The teapot in this image was crushed by a truck in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Bernhard “scooped” it up as she was running across the street.[xviii] She said, “she knew it was her teapot” and she kept it for many years before producing this print.[xix] Over the course of Bernhard’s career, she was also drawn to bones, shells, as well as dolls or doll parts. These were some of her favorite subjects which she brought to life with a dramatic use of light and shadow. Bernhard deliberated over her still life arrangements exploring the possibilities of a composition. She stated, “When I am working on a still life, it might be days before I make an exposure, and then it will be one negative. I see the image in mind’s eye. When the image in the camera matches it, I keep it on the negative.”[xx]

In the book Ruth Bernhard: Between Art & Life Bernhard states that the photograph Teapot from 1976 was her last exposure. Following a carbon monoxide poisoning in 1974, she lost her ability to “concentrate without enormous effort.”[xxi] Teaching became “really a substitute for making photographs” and a “vital” aspect of Bernhard’s life. [xxii] In the end “[she] came to believe that [her] teaching [was] more important than [her] photographs.”[xxiii] Bernhard stated, “While my photographs can burn up, my teaching is passed from one person to the next.”[xxiv]

Further Reading/Viewing:

Bernhard, Ruth and James Alinder, ed. Collecting Light: The Photographs of Ruth Bernhard. Carmel, CA: Friends of Photography, 1979.

Bernhard, Ruth. Gift of the Commonplace. Carmel Valley, CA: Lux 4-Woodrose Publishing in Association with the Center for Photographic Art, 1996.

Bernhard, Ruth, and Margaretta Mitchell. Ruth Bernhard: The Eternal Body: A Collection of Fifty Nudes. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books, 1986.

Kaplan, Ilee. Ruth Bernhard: Known and Unknown. Long Beach, CA: California State University, Long Beach, University Art Museum, 1996.

Mitchell, Margaretta K. Ruth Bernhard: Between Art & Life. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books, 2000.

Studies in Black and White: The Ruth Bernhard Papers. Princeton University.

Ruth Bernhard video. December 2013.

Ruth Bernhard at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (a selection of her work).

Notes: