Sarah Perry (American, b. 1956) is known for her ingenious animal-inspired sculptures that rely heavily on an array of found objects. She scavenges for materials, such as discarded truck tires or sun-bleached bones, and then skillfully transforms them into works of art that “communicate [her] subtlest emotions and deepest beliefs succinctly.”[i] The final result “can be [as] frightening as an uncensored dream, touch on the unknowable, or reflect the human capacity for awe.”[ii] In some cases humor can creep in as well.[iii] Over the years Perry has developed “her own distinct visual language, based on forgotten histories and the artist’s constant exploration of our universe, both terrestrial and celestial.”[iv]

EARLY YEARS

As a young girl Perry created things with seeds, grasses, and other natural materials that she found in her backyard.[v] Also, she remembers being drawn to “icky” stuff like bones, lizard skins, and bugs.[vi] Perry’s conservative parents thought this went “too far,” but she says she “swayed” them because they frequently liked what she made.[vii] By high school she was drawing very realistically and she seriously considered becoming a scientific illustrator. However, this idea was abandoned when Perry realized her true “love is sculpture.”[viii] She naturally “thinks in sculptural terms” and “just see[s] things three-dimensionally.”[ix] Perry attended the Otis Art Institute of Parsons School of Design in Los Angeles, California and graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 1983.[x] At Otis, “her childhood penchant for found objects returned” and she began combining this interest with “new techniques, new media, and new ideas.”[xi]

Following graduation Perry “burst onto the Los Angeles arts scene” with the creation of a group of gorilla sculptures.[xii] These life-sized apes were made of layers of old discarded car and truck tires that she found along the side of the freeway. Perry carefully arranged and fitted these rubber cast-offs over detailed welded steel armatures. The idea for these works came to her after seeing piles of trash along the highway and thinking “all this refuse is going to come back and haunt us.”[xiii] In Perry’s mind her “man-beasts” of accumulated rubber waste are rising up and making us “look at the carnage we wreak.”[xiv] She focused on the gorillas for about four years. Perry’s final work in the series was the 700-pound Gorilla Route #40, nicknamed Bill. The Los Angeles Times called this sculpture a “virtuoso performance” that truly “resonated” with audiences.[xv]

ASSEMBLAGE

The term assemblage was coined in the 1950s by the artist Jean Dubuffet to describe an art form that combines materials such as found or purchased objects. However, he was not the first to embrace this approach. As you study Perry’s body of work you cannot help but also think of Marcel Duchamp’s Readymades or Louise Nevelson’s monochromatic constructions made of scavenged lumber and other discarded wooden objects.

In California assemblage was a particularly important genre. Beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, artists, like George Herms or Edward Kienholz, “led the parade” creating compositions of “freely associated materials.”[xvi] These works could be “droll, provocative, witty, satirical – and sometimes, beyond the artist’s control.”[xvii] Perry, however, has been linked to a second generation of Los Angeles assemblage artists which includes individuals such as John Frame and Alison Saar. They garnered attention in the 1980s for their works that “cut, sawed, whittled, sanded, braided, and reshaped” found objects into “a recognizably different artifact[s].”[xviii]

While Perry acknowledges that she has “roots in assemblage,” “[she] no longer considers [herself] an assemblage artist.”[xix] This is because the found objects in her creations are “so altered and so sculpted” that she feels her work at this point “goes beyond” that original definition.[xx] If she had to pick a label for herself, it would be sculptor.

KAMM COLLECTION

The Kamms have acquired four of Perry’s works: Pontificate, Teapot C6, Darwin’s Portal, and The Miracle. It should be noted that only Pontificate and Teapot C6 are associated with the Teapot Foundation. The other two are part of the Kamm’s extensive contemporary art collection. However, in this instance, it seemed necessary to feature each of these examples in this blog post. Together these works, which were all produced in the 1990s and include a variety of found objects, reveal Perry’s range, ingenuity, and dexterity as an artist.

Perry does not usually create teapots which makes Pontificate (1999) as well as Teapot C6 (1996) unique. Teapot C6, which seems to cleverly reference the C6 vertebra in the human spinal cord, is an imaginative assemblage of collected animal parts and brass. The body of the form is a upside down tortoise shell and its handle is a vertebrae bone which is carved with small human figures. One end of the tortoise shell opens on a hinge, and the underside of the shell forms a spout-like feature.

Pontificate, on the other hand, is made of found objects, wood, and numerous examples of graniteware.[xxi] It is a whimsical teapot that contains a cylindrical body, a hinged iron handle, and a round lid. Protruding from its corroded weathered surface are also nine spouts. The graniteware body and spouts were found after scouring numerous desert dumps. Perry collected these various parts and then joined them together utilizing a wooden internal structure to provide stability. Inside the pot, on a section of that wood, is the text that reads, “Pontificate, Sarah Perry ’99 for Gloria & Sonny Kamm.” Over the years the Kamms have developed a personal relationship with Perry, and this work reflects their mutual affection. Pontificate was given as a “special present” to the Kamms after they helped support an exhibition catalog of the artist’s work.[xxii]

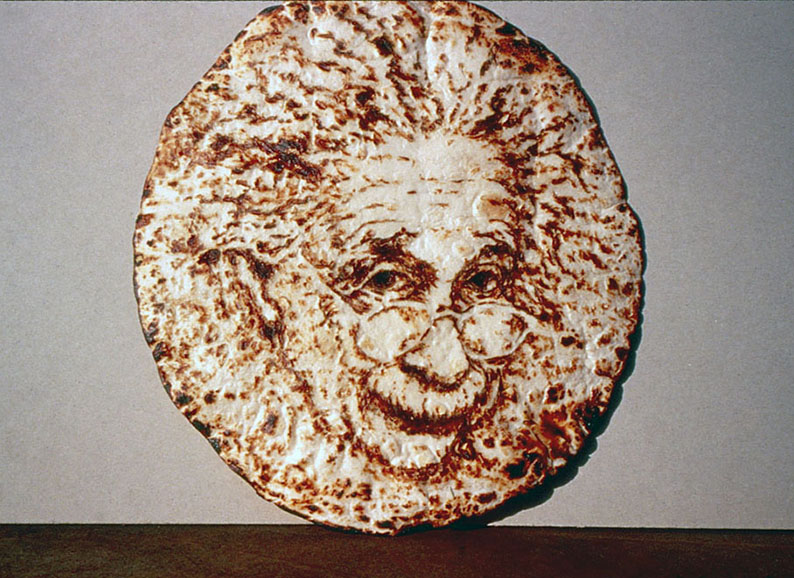

In 1998 the Kamms acquired The Miracle (1997) from Koplin Gallery in West Hollywood, California. In a divergence from animal bones, this work is simply a tortilla featuring the burned image of physicist Albert Einstein. Perry describes the process of making this work “really fun.”[xxiii] Using a little, cheap, wood burner, she carefully created Einstein’s face. Perry wanted it to look as if it naturally occurred or happened by accident. She then covered the tortilla in plastic which has preserved its integrity. The Miracle is playfully “making fun of religion” and the numerous miraculous discoveries that have come to light in recent years such as the image of Jesus on a potato chip or the face of the Virgin Mary on a grilled cheese sandwich.[xxiv] Perry thought, why not Albert Einstein? She mounted the tortilla on velvet, and it has a wood and acrylic case.

Last, but not least is Perry’s powerful work Darwin’s Portal (1997) which was acquired from Koplin Gallery the year it was created. From a distance one might think this is a carved stone sculpture on a pedestal, but once it is examined closely you realize it is made of thousands of tiny amphibian, reptile, and mammal bones which have been bleached white in the desert sun. These bones form a life-sized hand and wrist positioned upright. At the center of the palm, Perry placed an opening which is laced with arching bones. This translucent hole in Darwin’s Portal “carries overtones of crucifixion, alluding to suffering and death as an intrinsic part of life’s cycle of change, regeneration, and even evolution.”[xxv] Generally speaking, the sculpture “encapsulates the Darwinian theory of evolution” “in one quantum leap.”[xxvi] In addition, it reveals Sarah Perry’s innate ability as an artist to “mingle the beautiful with the abject, the precious with the repugnant, and the reasoned with the irrational.”[xxvii]

Futher Reading/Viewing:

Clark, Garth. The Artful Teapot. London: Thames & Hudson, 2001.

Kienholz, Lyn. An Interview with the Artist Sarah Perry. Netropolitan: Museum Without Walls. 13 November 2012.

Schulz, Max F. The Bone and Bird Art of Joyce Cutler-Shaw and Sarah Perry. Los Angeles, CA: University of Southern California, USC Fisher Gallery, 2007.

Notes: