“…If you [make art] based on what is stylish, or is acceptably good, then you have nowhere to take it.”[i] – Viola Frey

The American artist Viola Frey (1933-2004) is associated, first and foremost, with her monumental ceramic sculptures of men in suits and women in printed dresses. However, over the course of her lengthy career, she created an array of sculpture in clay, bronze, and glass as well as drawings, paintings, and photography. Frey, along with Robert Arneson and Peter Voulkos, is considered one of the giants of California Bay Area ceramics. In the 1950s and 60s, these artists “turned away from that medium’s conventional refinement to produce works with robust sculptural qualities associated with Abstract Expressionist painting, Pop Art, and what would come to be known as California Funk.”[ii]

During her lifetime Frey created work with “almost a compulsion.”[iii] That work, with its often “comic book aesthetic” and use of everyday imagery, is complex and filled with dichotomies.[iv] Frey’s oeuvre “[shifted] between childhood nostalgia and sophisticated perceptions, brilliant craft and high art, spontaneity and searching intellect, the local and the global,” and the monumental and the intimate.[v] This is an artist who embraced the figure, but like Joseph Cornell or Marcel Duchamp she also “composed amalgams of castoff “junk.’”[vi] Furthermore, while Frey’s work can be “anthropological in its references to popular culture, the visual arts, and the history of ceramics,” there is an autobiographical element prevalent as well.”[vii] A constant is her understanding of the power of color. Frey realized early on that color had the ability to “[intensify] an object’s participation in its surrounding space and light.”[viii]

LIFE ON THE FARM

Frey was born in Lodi, California to a farming family who had an old zinfandel vineyard. In this isolated rural community, she felt “[she] had to make her own culture.”[ix] In the farm’s irrigation ditches, Frey sculpted small cities in the wet sand and painted watercolors with one of her brothers. She also got art books and volumes of National Geographic from the local library. The National Geographic magazine was a window to the world. Within the publication Frey also found inspiration, especially in the images that featured the woman as a “figure of substance.”[x]

Life on the vineyard profoundly affected Frey’s future creative endeavors. Not only was the farm’s “rhythm of recycling” influential, but the massive amount of junk collected by her father and grandfather left a lasting impression.[xi] There were shacks filled with objects which ranged from hundreds of radios and TV sets to farm implements and tractors.[xii] Her father particularly liked machinery, which he brought home with the intention of fixing. Frey would also become a “passionate accumulator of everything.”[xiii] On her flea market visits she would “almost [obsessively]’ hunt through discarded bric-a-brac acquiring items such as ceramic figurines, books, and Indian miniatures.[xiv] Frey would come to see herself as a bricoleur, a concept and term that is derived from Claude Lévi-Strauss’ The Savage Mind.[xv] A bricoleur works in a “[devious]” manner “with odds and ends that are readily at hand and pertinent to [their] time, and…uses them to explore themes and tasks that [they find] compelling and interesting.”[xvi]

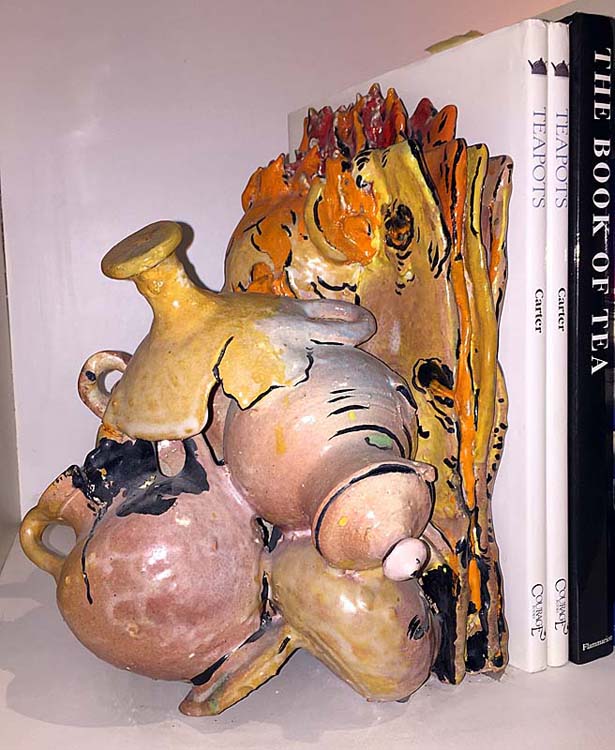

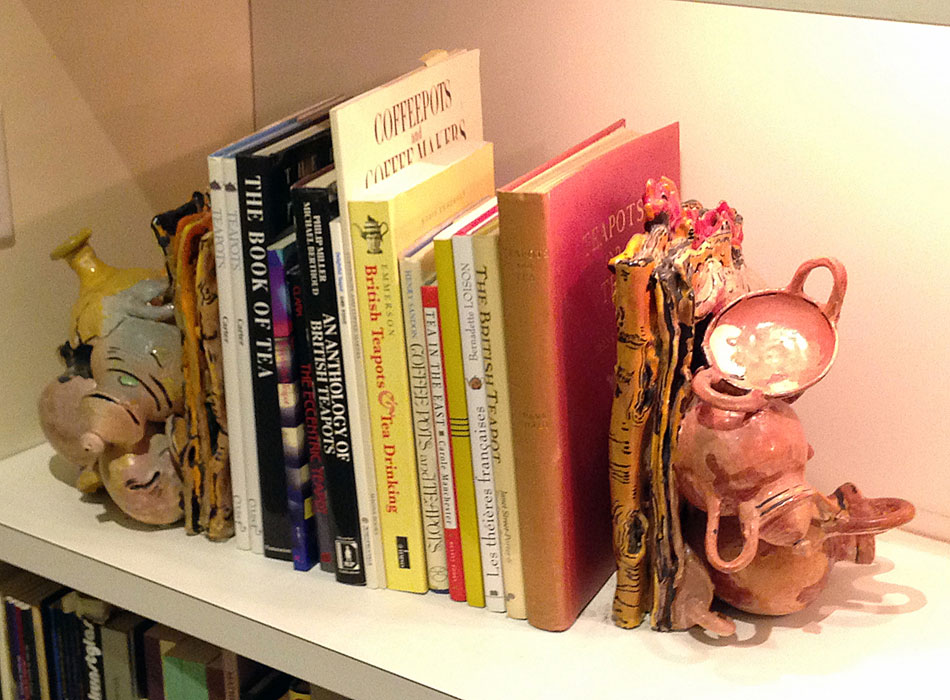

This bookend sculpture presents a jumble of ceramic pots, including some forms from ancient Greece. The Kamms acquired this Frey work in 1990 and have it displayed in their home library.

EDUCATION

In 1953 Frey enrolled at California College of Arts and Crafts (CCAC) in Oakland.[xvii] In art school she was conscious of the hierarchy between fine art and craft. “Frey disliked the word craft” and “refused to major” with that as a focus.[xviii] She was determined to be taken seriously so she decided to major in painting. At CCAC Frey studied with abstract expressionist painter Richard Diebenkorn. However, clay continued to speak to her. Frey took ceramics classes from Vernon Coykendall and Charles Fiske. From her perspective that department “had people of all ages in it. It seemed more like the real world. It was a community.”[xix] Frey received her Bachelor of Fine Arts from CCAC in 1955.[xx]

With a desire to further study painting and ceramics, Frey enrolled at Tulane University in New Orleans for graduate school. While at Tulane she was mentored by the sculptor George Rickey and “improved her mastery of clay” under the tutelage of potter Katherine Choy.[xxi] In addition, she participated in a workshop at the university with painter Mark Rothko. From Rothko, Frey learned about “the emotive qualities of color and its effects on the senses” and he reaffirmed the notion that “subject matter was everything.”[xxii] Ceramics would eventually become Frey’s “dominant medium.”[xxiii] She believed “what consciously attracted [her] to clay was that it utilized the disciplines of drawing, painting, as well as sculpture.”[xxiv]

EARLY STUDIO YEARS

Before finishing graduate school, Frey relocated to New York to work at the Clay Art Center in Port Chester. Founded by Katherine Choy and Henry Okamoto, the Clay Art Center “was like a commune but with a lot of direction.”[xxv] Frey said, “We all contributed to it.”[xxvi] They developed “one of the East Coast’s first organizations to allow artists to explore ceramics as a fine art rather than a craft medium.”[xxvii] During this period Frey also worked at the Museum of Modern Art to make ends meet and saw exhibitions that featured artists such as Pablo Picasso, Jean Dubuffet, and Alberto Giacometti. The work she encountered in those New York exhibitions would have a lasting impact on her aesthetically.

In 1960 Frey would return to the West Coast.[xxviii] The reason for her move was based on three factors: the pleasant weather, “the regional interest in the figure,” and her “good friend” Charles Fiske had relocated back there.[xxix] Frey took a job at Macy’s department store, and she continued her study of ceramics at CCAC. In essence, at this time she was “refining her vision as an artist.”[xxx] In 1969 Frey converted the basement of her house into a ceramic studio. She marked this as “the start of her serious artistic career.”[xxxi] Now Frey could work both two and three-dimensionally with “greater exploration and productivity.”[xxxii] In 1964 Frey became a teaching assistant in the ceramics department at CCAC and by 1971 she was an assistant professor. She would teach at CCAC until 1999 when she retired as professor emerita.

FREY TEAPOTS IN KAMM COLLECTION

There are two ceramic teapots by Frey in the Kamm Collection: an untitled work (1971-1972) and Venus and the Rooster (1975-1976).[xxxiii] These vessels not only show her “exploring different genres, mediums, and ideas,” but also, they reflect the influence of Frey’s training at CCAC. [xxxiv] Vernon Coykendall, who was head of the ceramics department there, believed that “all clay items had to have a purpose and a function.”[xxxv] This line of thinking stayed with Frey even as she began to explore the sculptural possibilities of clay. During the 1960s and 70s, she would often make functional vessels, like these works in the Kamm Collection, then add sculptural components. In essence, Frey was “bridging the functional with the sculptural.”[xxxvi]

The Kamm’s Untitled teapot has a domed body with a tall cylindrical neck and an upturned tubular spout. An animal bust serves as its lid and three mice climb on its surface. The animal inclusions reflect Frey’s ongoing sculptural interests as well as other aspects of her work at the time. She went through a “zoomorphic period” in which she created her acclaimed series called Endangered and Non-Endangered Species.[xxxvii] Inspiration for these works often came from Frey’s flea market excursions. She recreated and pulled molds from a range of creatures from dogs and deer to beavers and tigers.[xxxviii] This emphasis on animals really set Frey apart from other ceramic artists such as Robert Arneson who was focusing on more autobiographical topics at that time.[xxxix]

This particular vessel is also important because it shows Frey “beginning to formalize her long involvement with color studies.”[xl] While the teapot’s body and animal bust are covered in a pink glaze, the mice have a clear glaze with red details. In addition, there are spiraling rope-textured elements. These forms, which create the handle and are included on part of the lid, are strikingly coated in a reflective bronze-like luster glaze. Frey’s color studies, which were heavily influenced by her time with Rothko, would explore “the effect of volume upon light and color” and “make war on the static quality of sculpture.”[xli] For instance, she determined that “shiny highlights defined the forms and reflections within the colored glazes.”[xlii]

Viola Frey, “Venus and the Rooster” 1975-1976. Earthenware, glazes, china paint, 14 x 8.5 x 5.25 in. Kamm Teapot Collection 1996.1.37. Art © Artists’ Legacy Foundation. Images from the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue Living with Clay: California Ceramics Collections (2018) curated by Rody N. Lopez, CSU Fullerton, Begovich Gallery. Photographs by Eric Stoner.

The other teapot, Venus and the Rooster, features a colorful grouping of humans and animals, all of which appear to be modeled after flea market figurines in her personal collection. There are many items incorporated into this complicated sculpture including a statue of Venus de Milo, a rooster, a swan, a boy with a red bird, and a couple she would eventually call Mr. and Mrs. Wedgwood. These figures, some of which are seen repeatedly in her work, can provide layers of meaning, “reference a variety of cultures,” and even “have the ability to document lifestyles.”[xliii] In this teapot the classical Venus, which is the teapot’s handle, alludes to art history, antiquity, and female beauty while the rooster, which serves as the teapot’s spout, connects the work to her childhood on the farm as well as the male phallus. Together these two elements create a “yin and yang” within the sculpture.[xliv]

Furthermore, Venus and the Rooster illustrates Frey’s expanding explorations in color, specifically “the break-up of color and light.”[xlv] This interest was certainly impacted by the paintings of artists such as Jean Dubuffet, but her 1975 move to a new studio in Oakland, California was inspirational as well. There, in her backyard garden Frey had the opportunity to study her sculpture without a fixed light source. She watched the light move, saw how shadows were cast, and how this impacted the color. Inspired by this, Frey began to use her glazes and china paint “to surprise, distort, and dramatize.”[xlvi] In works like Venus and the Rooster, she seems to enhance these effects by leaving some areas unpainted and embracing, at times, a graphic sensibility. The clay surface is treated like a canvas with a “push-pull relationship between reality and abstraction.”[xlvii] Ultimately, painting would have a “great influence on her ceramics.”[xlviii] For Frey, “ceramics, drawing, painting, [and] sculpture [formed a] total means of expression.” She firmly believed that “…each field of creative activity …enhances the other.”[xlix] Venus and the Rooster is perhaps one of the last teapots Frey created.[l] By the late 1970s she had shifted her focus from assemblage to the figure creating acclaimed large-scale sculptures such as Double Grandmother and Mrs. National Geographic.

Further Reading/Viewing:

Clark, Garth. Viola Frey Retrospective: Creative Arts League of Sacramento Presents California Crafts XII. Sacramento, CA: Creative Arts League of Sacramento, 1981.

Gallery Talk: Gods & Monsters. 21 May 2020. American University Museum.

KQED Spark – Viola Frey. 19 January 2016.

Kuspit, Donald. Viola Frey: Plates 1968-1994. Nancy Hoffman Gallery, 1994.

Living with Clay: California Ceramics Collections This exhibition at California State University, Fullerton and its accompanying catalogue (see below) featured collectors like Sonny and Gloria Kamm and the ceramic objects they have collected. The work Venus and the Rooster was included as well as two bookends that the Kamms have in their personal collection.

Lopez, Rody N. Living with Clay: California Ceramics Collections. Fullerton: California State University Fullerton, 2018.

Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art’s Viola Frey Oral History Project.

Taragin, Davira. Bigger, Better, More: The Art of Viola Frey. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 2009.

Viola Frey. Rena Bransten Gallery. San Fransico, CA: Rena Bransten Gallery, 1998.

Viola Frey Oral History. Smithsonian Archives of American Art. Conducted by Paul Karlstrom. 27 February, 15 May, and 19 June 1995.

Viola Frey: The Bricoleur. Artists’ Legacy Foundation. 18 November 2022.

Notes: